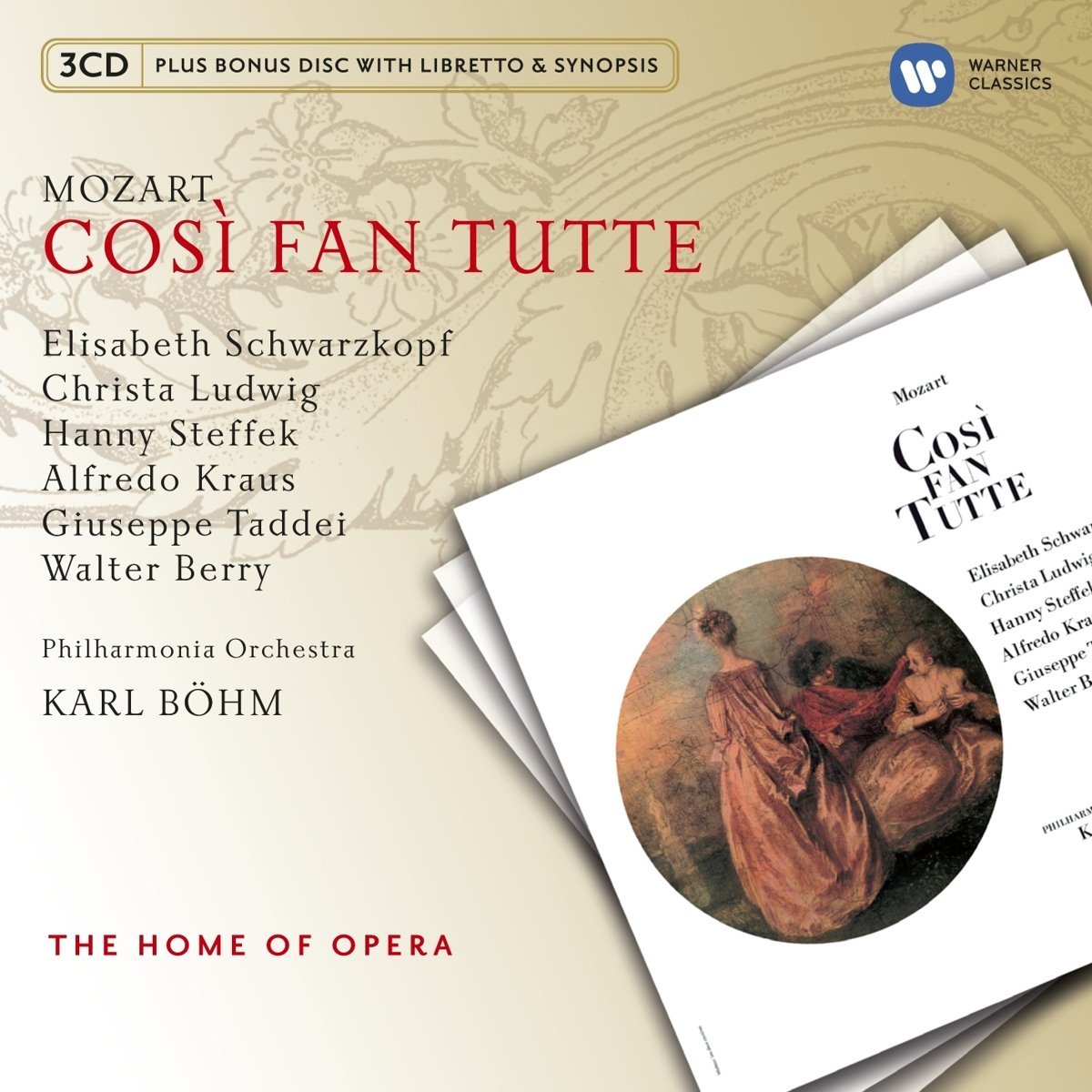

Opera: Cosi fan tutte (“They all do it”)

Composer: Mozart

Other popular works by this composer: Don Giovanni, Die Zauberflote, Le nozze di Figaro, Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail, Idomeneo

First performed: 1790

Language: Italian

Accessibility Level: Beginner Explorer Aficionado

Setting: 18th century Naples

Plot: A man bets his two friends that their fiancées would not remain faithful if the men were sent away; they fake absence and disguise themselves as new suitors to find out

Highlights: Soave sia il vento, Un’aura amorosa, Dammi un bacio, Secondate aurette amiche, Il core vi don

Recommended audio recording/s: Schwarzkopf/Ludwig/Krauss/Bohm; Watson/Montague/Spence/Mackerras (in English)

Recommended video recording/s: Lehtipuu/Pisaroni/Persson/Vondung (Glyndebourne)

Rating (1 to 5): ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Apparently, fiancée swapping was a popular theme back in the day (and you thought everyone was so innocent back then), and I have to say the plot of this opera seems a bit unusual today. What’s more, the implication is made that women are unfaithful, the reverse of the prevailing attitude of our own time. Once you get past these two cultural hurdles and realize that times and attitudes change, perhaps you can enjoy the show. Remember, they didn’t have much to titillate themselves back in the 1700s, so this was likely their version of Girls Gone Wild.

Another thing I have to get out of the way on this one is recitative, because it crops up a lot in works of this era (the late 1700s/early 1800s). In case you’re unfamiliar with it, recitative is the half-spoken, half-sung dialogue part of many operas. It basically helps explain and advance the plot, and is interspersed between arias and other more formal musical numbers. Some operas have a little of it, some a lot. The problem with it is this: it is not particularly interesting to listen to, especially if you don’t understand the language, which will often be the case. Also, much of it sounds the same; there’s not enough variety to make it captivating. When it’s accompanied just by piano plinking, it’s especially annoying. Here’s an example:

If you’re watching a subtitled video or a supertitled performance where the words are translated, this isn’t a problem and the recitative will actually add to your understanding and enjoyment of the show. But if you’re just listening and not following along with a translation, the recitative will likely bore you to tears. In fact, I suspect this is one reason why many people have never listened to an entire opera. Even at my level of familiarity, I find recitative tiresome if I’m just listening, as opposed to watching a video. So my trick is this: I make myself a recording with the recitative eliminated (the spoken parts are usually separate tracks on most opera recordings, so this is easy to do). This leaves me with just the musical numbers and very few tedious parts. In the case of Cosi fan tutte, this made a huge difference in my listening pleasure (it’s a good thing to do with Rossini operas as well). Of course, this is also why they sell opera “highlight” discs; they basically accomplish the same thing, though go a bit further in cutting some music as well.

Perhaps because of all this, Cosi did not appeal to me initially. The music didn’t hook me immediately as did that of Mozart’s Die Zauberflote or Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail, and the story seemed too outlandish to be credible (really? you don’t recognize your own lover in disguise?). I had to listen to it numerous times (and to several different recordings) before it took root, which is a shame because the music is beautiful. Sure, a few arias stood out immediately, but it was a while before I came to appreciate the work as a whole. Incidentally, I’ve had the same problem with Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, which many people love but I’m not yet impressed with. As for Don Giovanni, again not an instant favorite, but after a few listens I recognized it as a complex masterpiece.

The overture to Cosi isn’t nearly as well-known as the ones to Figaro or Don Giovanni, but it’s more than adequate. The piece is lively and rather boisterous, and, unlike some overtures, actually quotes parts of the opera to follow. Some composers, like Rossini, actually used the same overture for several different operas. Hey, why not? There was no sound recording back then, and people were lucky to see a particular opera once in their lifetime, so they’d likely not remember a recycled overture!

We open with our two male leads, Ferrando and Guglielmo, extolling the virtues of their lovers, Dorabella and Fiordiligi, respectively. Now some of these names are tongue twisters, so bear with me (I keep wanting to call Ferrando Fernando, thanks to ABBA). The good news is that there are only six main characters, so it doesn’t get too terribly complicated. The men’s friend, Don Alfonso (not to be confused with Don Alonso from Il Barbiere di Siviglia!) has a more pessimistic view of women, and bets the men that their lovers would not remain faithful were they to leave them for even a day, given the proper temptation. The men accept the wager and agree to pretend to be sent off to war. They will then don disguises and attempt to woo the other friend’s woman (yeah, it’s implausible, but so are most opera plots!).

Soon we come to an aria that is so sublime, so beautiful, so delicious, that it may bring tears to your eyes. It’s pure Mozart genius, the composer doing what he does best – light, tender melodies that just float on air (and, in the case of this one, floating on air is exactly what he was trying to convey). It stood out to me immediately the first time I listened to this opera, and, along with one we’ll hear next, is a major highlight of this work. It’s called Soave sia il vento (be gentle, breezes), and is sung as the women wave goodbye to their lovers, who are off to war:

The men “leave” and the scene switches to their home, where we meet Despina, their maid (did everyone have maids years ago?). Don Alfonso is afraid Despina will spill the beans and recognize the disguised men, so he bribes her into going along (and why wouldn’t their fiancees also recognize them? This isn’t addressed). The men enter dressed as Albanians (which apparently means they’re hairier), and the women are taken aback. The “strangers” profess their love, but the women remain steadfast. Ferrando senses victory, and sings the second amazing aria from this opera, Un’aura amorosa (a loving breath). Here it is, sung by the dashing Finnish tenor Topi Lehtipuu:

The men threaten, and pretend, to drink poison if the women won’t give in to their wooing. A fake doctor (really the maid, Despina) revives them with magnet therapy, a contemporary reference to the then-popular work of Anton Mesmer, from whom we get the term “mesmerize.” The men demand a kiss, but the sisters refuse. However, after some encouragement from Despina, Dorabella starts to weaken and Fiordiligi agrees that some mild flirtation would do no harm. The men present them with flowers to this gentle tune, Secondate, aurette amiche (help them, gentle breezes):

Fiordiligi caves in just as her sister did, and a notary is summoned (again, Despina in disguise) to perform a double-wedding (how quickly these relationships progress! Well, people did die young back then . . . ). The documents are signed, and soon after we hear military music indicating the “return” of the two men who supposedly went off to war. The “Albanians” flee, change out of their disguises, and return to profess their love for their sweethearts. When Don Alfonso shows them the marriage contracts, they feign outrage before revealing to their lovers that they were the Albanians all along. Don Alfonso has won his bet – women are supposedly unfaithful (cosi fan tutte!), but all take it in stride and make up. Implausible? Absolutely! But the music is gorgeous, almost too eloquent for such a silly plot. This one is perhaps better listened to than watched – just be sure to edit out those boring dialogue parts!