Opera: Pique Dame (The Queen of Spades)

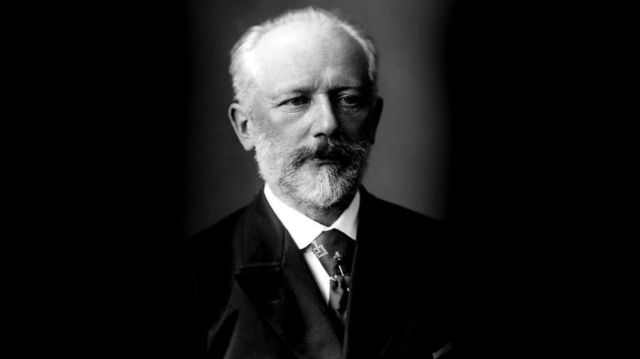

Composer: Tchaikovsky

Other popular works by this composer: Eugene Onegin

First performed: 1890

Language: Russian

Accessibility Level: Beginner Explorer Aficionado

Setting: Late 1700s, Russia

Plot: A man dually obsessed with gambling and another man’s woman finds he is unlucky in both cards and love

Highlights: Ja vas lyublyu, Akh! istomilas ya goryem, Je crains de lui parler la nuit

Recommended audio recording/s: Rostropovitch, Ermler

, Gergiev

Recommended video recording/s: Didyk, Magee; Liceu

Rating (1 to 5): ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tchaikovsky wrote about a dozen operas, only two of which are popular today. He was much more successful in other genres (symphonies, ballets, orchestral pieces), in which he was proficient and phenomenal. Of his two popular operas, most would probably agree that Eugene Onegin is his claim to fame, if only because it is the one with which most people are familiar (according to Operabase, Eugene Onegin is currently the sixteenth most popular opera in the world; Pique Dame is forty-eighth). Onegin is performed much more often than The Queen of Spades, but I think the latter opera is far superior. Tchaikovsky himself agrees with me – he thought it his best work, which at this stage in his career is saying quite a lot. It is my favorite opera of the scores with which I am currently familiar, and one of the few that I enjoy in its entirety. There are no dull moments (which so many operas have, and which is probably why the art form is not more popular) thanks to Tchaikovsky’s wonderful facility with melody and drama, which is on full display here. This work is one thrilling scene after another, all the more amazing when you learn that Tchaikovsky wrote it in six weeks’ time.

The opera is at turns grand, dramatic, majestic, exciting, plaintive and mournful, much like Tchaikovsky’s best symphonies. It has a bit of everything. The arias and melodies are stunningly beautiful, and the orchestral writing is full of Tchaikovsky’s distinctive flair for drama and pathos. The music takes center stage here – how could it not in Tchaikovsky’s hands? Listen to this delicious opening to Act III as you continue reading:

This was the first opera I ever saw live, back in the early ’90s, during my very first and thrilling visit to the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center in New York City. Russian opera is not a typical first choice for people new to the genre, as I was, but I was enormously moved by Tchaikovsky’s symphonies and life story. He was my hero, and I had a burning desire to see one of his operas, so I headed to New York. This was right around the centenary of his death, and his music was even more in vogue than usual. But it was mid-February, and a blizzard hit the city during my stay. The opera was on a weeknight, and between that, the storm, and this opera not being wildly popular, the opera house was relatively deserted. I was able to move to a prime seat up front that would have normally cost a small fortune, and was far better than the one I had paid for. For the next three hours, I was mesmerized and enthralled by this highly atmospheric, haunting opera. Not only was the music passionate and visceral, but I felt like they were playing it just for me. When I hear certain parts of the opera today, I am strongly reminded of that magical, snowy night when I was warmly cocooned in the splendor of one of the greatest opera houses in the world, feeding my soul with a work of immense genius.

The opera is the story of a (literally) haunted man, Herman, who is addicted to gambling and to discovering the secret three cards that will supposedly win him a fortune. The secret is rumored to be known to an old Countess (the “Queen of Spades” of the title), who also happens to be the grandmother of the woman Herman is in love with (Liza) but cannot have (she is betrothed to a prince, and Herman is not of her class). The opera is based on a story by the great Russian author Alexander Pushkin, just as Tchaikovsky’s other popular opera, Eugene Onegin, is, but this time Tchaikovsky’s own brother wrote the libretto, with some help from the composer himself. Tchaikovsky composed this opera around the same time as his extremely popular ballet The Nutcracker, and each shares similarities. The composer would be dead in just three years’ time at the height of his career, so this is among his last compositions. There is so much glorious music in this opera that I can’t include it all here; I’d basically be posting the whole thing (you can indeed watch the whole thing on YouTube. I’d highly recommend this one). This opera’s music goes directly to the depth of my soul, like so much of Tchaikovsky’s output, and leaves me awestruck with its brilliance. Whether these feelings are vestiges of that impressionable night in New York many years ago – my first opera, my first time at the Met, the allure of the City – I’m not sure, but this is one I treasure deeply. It is my desert island opera, and you won’t find me paying more rapt attention to anything else.

The opera begins with some foreboding chords in the overture, followed by a pleasant opening scene in a park on a sunny day (this scenario is very reminiscent of the opening scene in The Nutcracker). Children play as the governesses watch over them and the men discuss the happenings at the gambling tables the prior night. They remark on Herman’s obsessiveness and recent moodiness. He admits to being in love from afar with a woman whom he has not officially met (Liza). He soon discovers that she is above his station, and is pledged to another, Prince Yeletsky. There is a wonderful quartet in this scene (“mne strashno” – “I am afraid”) between Herman, Liza, the countess and the prince wherein they each voice their respective fears (timestamp 23:40):

The scene switches to Liza’s home, where she and her friends are singing some musical numbers at the piano. Two of them have a pensive, forlorn theme, and the last is frivolous to lighten the mood. None of them do anything to advance the plot, except to highlight Liza’s unhappiness with her engagement. Rather, they are excellent pieces to create a mood (both happy and sad, as Tchaikovsky excelled at these extremes) and to show off the composer’s talent for melody. Here, in succession, is each number, starting at 35:20:

After all this singing Liza heads for bed but can’t sleep. She’s thinking about the mysterious stranger she saw in the park (Herman), who suddenly appears on her balcony. He basically tells her that he will kill himself if he can’t have her, and guilts himself into her arms. Pathetic, but hey, that’s opera sometimes (OK, much of the time).

The scene switches to a ball being thrown by the prince to celebrate his engagement to Liza. Here, the prince sings the opera’s famous love aria, ja vas lyublyu (I love you madly), probably the most famous number from any of Tchaikovsky’s operas, and a highlight of his considerable opus. The first clip below is the rousing opening to Act II, and the second is the aria, sung by the wonderful (and recently deceased) Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky:

The masked ball continues with a charming pastorale (a rural musical play) to entertain the guests, complete with sheep. Meanwhile, Liza gives Herman the key to her room, and he makes plans to visit her that night. The master of ceremonies of the ball announces that Catherine the Great is about to grace them with her presence, and Tchaikovsky gives us a thrilling, frenzied buildup and crescendo to herald her majesty’s arrival. This scene, when done right, is just fantastic (the one on the Boder/Didyk disc is my favorite, but not available online). In the clip below there is no physical empress, just an image, but you’ll get the idea. It’s at 29:14:

In the next scene, Herman is in the countess’s room, just outside Liza’s, mulling over his fate, captivated by a portrait of the younger countess on the wall. He hears the countess arriving and hides. She sings a haunting number in French about the days gone by, Je crains de lui parler la nuit, (I’m afraid to speak to him at night) at 42:43:

Herman reveals himself after the countess dozes off, and threatens her with a pistol to get her to reveal the secret of the three cards. She dies of fright. Liza finally gets home, and thinks that Herman was only using her to get to the countess. She asks him to leave. Now he is without the secret or the girl – he just can’t catch a break.

Act III opens with another example of Tchaikovsky’s prodigious talent for expressing emotion with musical instruments. I provided a clip of this at the beginning of this discussion, but here is another one for good measure, in the venerable Russian conductor Valery Gergiev’s capable hands. Listen to it as you read the following paragraph.

Herman receives a letter from Liza asking him to meet her by the river at midnight. Below is the dramatic scene, and Liza’s pliant hope that Herman still cares for her. One can imagine Tchaikovsky himself, who was no doubt tired of hiding his homosexuality all his life and was prone to depression, echoing these words that he penned for Liza: “I am weary . . . worn out with suffering. I am exhausted by grief; night and day I have been tormented by thoughts of him. Where is the joy I once knew? I am weary, so tired. My life promised me only joy; then clouds gathered. A storm carried off everything I loved in the world, destroying my happiness and my hopes . . . ” This aria is chilling (it begins after the dramatic introduction, and after she descends the stairs, at 12:32).

Suddenly the countess’s ghost appears to Herman, telling him that she is compelled to reveal to him the three secret cards: three, seven, ace. Herman goes to meet Liza, but is consumed with his newly learned secret instead of with her. Feeling abandoned and forlorn, she leaps into the river (well, in this clip she kind of just vanishes) as he hurries off to the gambling hall at 23:20. Yes, there’s lots of codependency in these operas, which helps the drama along:

Herman arrives at the gambling hall, ready to play his secret cards. He bets heavily with the three, then the seven, and wins both hands. He then bets it all with what he thinks is the ace, but it turns out to be the queen of spades – the countess’s revenge. He loses it all and, depending on the version you watch, ends up insane or kills himself. Here, at the opera’s mournful conclusion, his comrades pray for his tortured soul. This is so moving that Tchaikovsky himself wept as he wrote it – again, perhaps, it was too close to home. Listen to it (timestamp 40:20) as you read my closing thoughts on this very personal work.

There you have it; a moving, dramatic masterpiece full of beautiful music and pathos; Tchaikovsky’s best opera. One can only wonder what else he would have created had he lived beyond the age of 53, considering that this and two of his other masterworks – the Sixth Symphony and The Nutcracker – were all created in his last few years. But maybe this was all he had in him – after all, how much genius can a genius produce? Perhaps he said all that he had to say. As someone who has read extensively on this talented man as well as spent countless, blissful hours listening to his incredible music, I am convinced that he had had enough of life, and knew his end was near (there has always been speculation that he passively killed himself). I think Liza’s lamentation, quoted above (“I am exhausted by grief”), is his vicarious, mid-life suicide plea, and his mournful Sixth Symphony a few years later only cements this theory. In any event, I am eternally grateful for everything he had to say in his music, both hopeful and hopeless, to me and to the world. He spoke both languages, but the latter ultimately prevailed.

Sound recording was just being invented when Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky died from cholera on November 7, 1893, after foolishly (purposely?) drinking a glass of unboiled water during an outbreak. There is a very brief recording of his voice on a wax cylinder that resides at the Tchaikovsky Museum in Russia at the site of his final residence. It is indistinct, high-pitched and full of static. But no matter; his passionate music speaks for him far better than any words could. As he was fond of saying, “where words leave off, music begins.” Pyotr Ilyich, may your troubled soul rest in peace. Ja vas lyublyu.

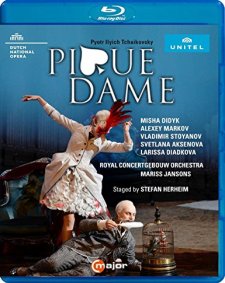

A word on available audio and video recordings of this work: For audio, my top recommendation would be the fantastic Rostropovich set, followed by conductors Ermler and Gergiev. For video, the YouTube recording mentioned above (led by Gergiev, with Vladimir Galouzine as Herman) is superb, but sadly not available commercially. However, you can watch the whole thing on YouTube – the video and audio streaming quality is excellent. Just be aware it is in three separate parts. This recording has many dramatic touches that I really like, and Galouzine is fantastic as Herman, both in voice and acting. On disc, the best choice is the Liceu/OpusArte recording (with Misha Didyk as Herman). It is visually and audibly stunning. The costumes and sets are fantastic, and this Herman (Didyk) isn’t too hard to look at (unlike some of them!) The 1992 Gergiev performance with Gegam Grigorian as Herman is also worthy, if a little dated. The Metropolitan Opera 1999 recording with Placido Domingo as Herman and Valery Gergiev conducting has not, as of this date, been released.

Update: Review of the Dutch National Opera Pique Dame DVD:

This unconventional performance takes many interesting liberties with Tchaikovsky’s penultimate opera (and my favorite of all the operas I know). However, these changes would be very confusing to those not familiar with both the opera and with Tchaikovsky’s personal life, which has always been an integral part of his major works. Being familiar with both, I was able to appreciate much of the symbolism in this performance, even if it was occasionally distracting. The modifications were at times clever and thought-provoking, at other times silly and cringe-worthy. I’ve always imagined Tchaikovsky to be a reserved and dignified man, so it bothered me to see the singer portraying him behaving contrary to this image. Yes, the composer himself has a strong presence in this performance, and I don’t mean metaphorically. His character is on stage most of the time, with mixed results. He observes, writes, dances, conducts and even sings (and quite well at that). The concept is very intriguing since, as I mentioned, Tchaikovsky the man is so intricately tied up in his works, and particularly this one. I’ve always felt that Lisa’s pessimistic lamentation by the river in her plaintive Act III aria (I’m so weary . . .) was a stand in for Tchaikovsky’s own vicarious emotional catharsis, and it may even shed some light on his state of mind just three years before his untimely death at age 53.

“Tchaikovsky” interacts with others on the stage without being overly intrusive. In fact, it’s a bit surprising how well this fits into the overall work. He is at times inspired by the happenings in front of him, usually leading to flourishes of creative thought. He basically abducts the role of Prince Yeletsky, even to the point of singing his (and this opera’s) greatest aria, with wonderful effect. To see this character, who looks so much like the real Tchaikovsky physically, so immersed in his own work was deeply moving at times. In fact, there is a whole cadre of Tchaikovsky look-alikes on stage, identically dressed and making the point very clearly that this opera, written by Tchaikovsky and his brother Modest, takes many pages from Tchaikovsky’s own life experience.

The curtain opens on a beautiful drawing room set that serves as the setting for most of the action (Tchaikovsky’s living room, Lisa’s bedroom, the Prince’s ballroom . . .). This also works surprisingly well, and allows for a refreshing change from the standard strolling-in-the-park venue of the traditional opening scenes. Tchaikovsky has just finished satisfying his sexual urges with a male prostitute (whose identity is quite intriguing), and with that uncomfortable moment the overture begins. This was one of those cringe worthy scenes, a bit jarring (“too much information,” as they say, and certainly not part of the opera as written), but probably not that far from the truth of Tchaikovsky’s actual life experience. Nevertheless, I felt my idol was being shamed for his natural inclinations, but I think the intent was more likely to highlight his own shame at being homosexual in such a repressive time and place – a time when his proclivities were so unacceptable, especially for a man of his class and notoriety. This repression was certainly a huge factor in his musical creations and emotional life, and without it we would not have his glorious opera – and here I invoke the true Latin meaning of this word (“opera,” the plural of “opus”), which is the sum of a composer’s creative works.

Creative touches I really liked include Tchaikovsky directing the child soldiers in the opening scene; him conducting the chorus (something he did in real life) and playing the piano during some of his most intensely emotional music; and the inclusion of references to Mozart’s opera Die Zauberflote, a work that had just been written (in Pique Dame’s time frame, the 1790s) by another musical genius whom Tchaikovsky greatly admired. All of these make sense, as does the parallel between Lisa’s unhappy betrothal to Prince Yeletsky and the real-life betrothal of Tchaikovsky to a woman whom he did not love and had little true interest in, except to quell gossip. Lisa jumps in the river, and so did the real Tchaikovsky (well, sort of, in a lame and thankfully unsuccessful attempt to kill himself).

One striking quirk about this production is that I watched the entire thing before I realized, only by glancing at the disc’s cover, that the man who played Herman, Misha Didyk, is the same man who played him in the Liceu production six years earlier, which I had watched just last week. He was unrecognizable to me, and I still have a hard time believing it’s the same person. In the former production he was dashing and handsome, in this one he looks sloppy and unkempt. Maybe the long hair just doesn’t work for me; it was no doubt meant to make him look more girlish (or more Danish?)

By the end of this performance, I had grown tired of the insertion of Tchaikovsky into every scene; it became distracting. He was too much of a focus, and it detracted from the telling of the story. He is on stage for almost the entire three hours (he must indeed be “weary,” as his aria complains). While there were some nice dramatic touches in the latter scenes – the smoke-spewing, swinging chandelier and lighting in the ghost segment, and the ghost speaking through Tchaikovsky was a deliciously eerie addition – it was not enough to keep me from being weary. Maybe I’ve just watched too many Pique Dames this month, but I prefer the traditional interpretations. I would not recommend this for a newcomer to the opera. Not only would they be utterly confused by the modified story line, but while that modification adds some intriguing twists for aficionados to chew on, it also takes away the charm and cohesion of the original. Certainly worth a look by seasoned viewers, but if this had been my only experience with the opera I may not even have liked it, and it certainly would not be my favorite opera of all time. If you want to know the real Tchaikovsky, he is right where he has always been – in his glorious music, not romping around on stage.

Also reviewed: Fedoseyev-conducted 1989 performance (recommended)

Pingback: Eugene Onegin | Opera for Beginners