Opera: Les Contes d’Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann)

Composer: Jacques Offenbach

Other popular works by this composer: Orphee aux enfers, La belle Helene, La Perichole

First performed: 1881

Language: French

Accessibility Level: Beginner Explorer Aficionado

Setting: Bavaria, Germany

Plot: A tortured poet recounts his disastrous past love affairs

Highlights: Chanson de Kleinzach, Entr’acte

, Les oiseaux dans la charmille, Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour

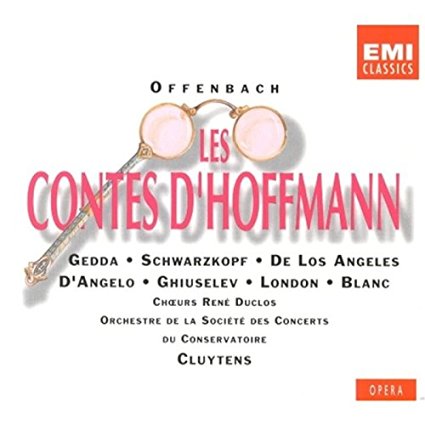

Recommended audio recording/s: Gedda/Schwarzkopf/de Los Angeles/Cluytens

Recommended video recording/s: None yet!

Rating (1 to 5): ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

You know Jacques Offenbach. Yes you do. He wrote the famous and wildly infectious Galop Infernal (more popularly known as the “can-can”) burlesque number from Orpheus in the Underworld. He also wrote many operettas, some that were quite risque for the time and that delighted in poking fun at French society (much as Gilbert and Sullivan liked to do to English society). The Tales of Hoffman was his last opera; in fact, he died before finishing it, in spite of his desire to live long enough to attend its premiere. It is arguably his most popular work, even if the plot is rather hard to follow (this is not at all unusual in the opera world – the plots can be quite convoluted!) God knows I had to listen to, view, and read up on this opera numerous times before I was entirely sure what was going on! The music, however, is wonderful, as Offenbach really knew how to write and work a melody. And be irreverent. That, however, is kept largely in check in Hoffmann. Not that I mind a good dose of irreverence.

The namesake of this opera was a real person, E.T.A. Hoffmann, the German writer best known for penning the tale that ultimately became The Nutcracker. Hoffmann’s stories often invoke fantasy, as is the case with both The Nutcracker and the opera presently under discussion. The opera makes use of three of Hoffmann’s supernatural tales, framed by the author himself who is recounting them as if he personally lived through them. In each tale, he is in love with a woman whom he cannot have, thwarted by a nemesis, and ultimately left humiliated and devastated. This is, presumably, pure fiction (he was married but died of syphilis, so make of that what you will).

What makes keeping track of this seemingly simple plot difficult is that there are a large number of similar characters, many of whom are essentially the same person (in some productions, literally the same person, in different disguises), or at least personifications of the supposed loves and struggles in Hoffmann’s life. In the outer story that frames the three tales, his muse (his poetical inspiration), a woman, transforms into his best friend Nicklaus, a man (this role is consequently sung by a woman, dressed as a man). She/he aims to win Hoffmann for her/himself so that he will keep writing and forget this silly love business. Confused yet? You will be before we’re through (and I skip a lot of the details). Let’s begin.

The opera starts off in a bar where an opera (Mozart’s Don Giovanni) is being performed on an adjoining stage. The patrons rush in during intermission to drink and toast the new prima donna, Stella, whom Hoffmann is in love with. However, so is the sinister Councilor Lindorf. Stella sends Hoffmann a note and the key to her room; Lindorf intercepts it. Hoffmann then entertains his drinking buddies with a colorful song about a dwarf named Kleinzach, the opera’s first well-known number that has absolutely nothing to do with the rest of the plot:

Before we get into the bizarre details of the tales themselves, I must mention the delightful entr’acte that takes place before they begin. An entr’acte (French for “between acts”) is a brief musical intermission that sets the stage, as it were, for the next act, much like an overture sets the stage for the whole work. It’s like a musical hors d’oeuvre (in keeping with our French theme!) Not all operas have entr’actes but many do, especially the French works (Carmen has some famous ones). This opera has four of them, and the first is wonderfully upbeat and joyous. It is also sung later on in the act by a chorus, to rousing effect. Here it is in the instrumental form:

Now that the stage is set, Hoffmann proceeds to tell of his three loves (not counting the aforementioned Stella). There are numerous versions of this opera (thanks to Offenbach not totally completing it), and the three tales are not always told in the same order. However, the first one is almost always the tale of Olympia, a mechanical doll created by an inventor named Spalanzani and his buddy Coppelius. Hoffmann does not know Olympia is just a lifelike doll because of special glasses he is wearing (given to him by his nemesis in this act, Coppelius) that make her appear real. He promptly falls in love with her. The doll sings a famously difficult aria, Les oiseaux dans la charmille (a.k.a. “The Doll Song”), having to be wound up several times when she starts to run down. This is a comical showpiece in the hands of more gifted performers and a real workout for the soprano in terms of acting, moving stiffly and singing the difficult passages:

Hoffmann’s nemesis destroys the doll out of spite and everyone laughs at him for having loved an automaton. Next up (depending on which version you watch) is the tale of Hoffman’s love for Antonia, who is sick and forbidden to sing by her father, Crespel, as it makes her weaker. The incarnation of Hoffmann’s nemesis in this scene is the sarcastically-named Dr. Miracle, who promises to make Antonia better but actually forces her to sing, which kills her. One of the highlights of this act is the comic performance of Frantz, Crespel’s somewhat inept and flamboyant servant (gotta love the French – watch this!):

The last tale opens with the opera’s most famous number, a barcarolle or boat song called Belle nuit, o nuit d’amour (beautiful night, oh night of love), which you have surely heard before. I have posted two videos of it below, one instrumental led by the wonderful French conductor Georges Pretre, and one vocal sung beautifully by Anna Netrebko and Elina Garanca. Gorgeous!

This final tale involves Giulietta, a courtesan (a nice word for a high-class prostitute). She pretends to love Hoffmann, but is really doing so to get a diamond ring offered by his nemesis, Dapertutto, who wants her to steal Hoffmann’s reflection (I’m still not sure why). She does so, abandons Hoffmann, and ends up dying like the other two lovers. Poor Hoffmann! Foiled and embarrassed again!

We come full circle to the same tavern that opened the story, where Hoffmann swears off of women (who can blame him at this point?) His friend Nicklause reveals himself to really be his muse, who loves him. Hoffmann returns to her, and poetry, and the devious Lindorf (represented by the evil men in each of the tales) leaves with Stella, Hoffmann’s original love – different aspects of whom were also personified in each of the tales (in some productions the three evil men are played by the same singer, as are the three women. The latter is rarer, however, due to the very different types of singers required for the women).

I highly recommend the recording of this opera pictured at the top of the page, led by French conductor Andre Cluytens. I have listened to numerous renditions of this work, and the Cluytens recording is a clear favorite. The music stands out in terms of the drama, tempo and reverence that Cluytens expertly imparts on this delicious score.

There is no recording of this opera in English, so if you want to follow the complex story (bless you) you’ll have to read along with the libretto and its translation (included with most CDs), or watch a video performance with subtitles, which is far easier. The Metropolitan Opera performance I’d recommend, from which the doll song above is excerpted, is not yet available on DVD. Of course, you can also just listen to the wonderful music without following the plot, as I often do. Until next time, bon apetit!